The following is the obituary of Honey Lee Cottrell written by Brenda J. Marston of the Human Sexuality Collection, Cornell University.

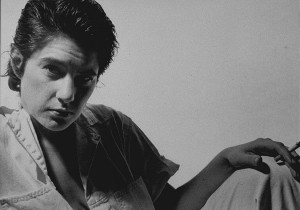

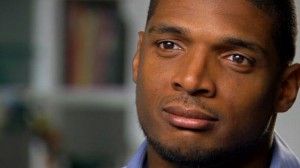

Honey Lee Cottrell. 1978. Image by Tee Corinne.

Honey Lee Cottrell, a visionary photographer and filmmaker who pioneered lesbian erotica in the 1980s through her contributions to the women’s sex magazine On Our Backs, died on Monday, Sept. 21, of pancreatic cancer.

Cottrell revolutionized the female nude, validated women’s right to pleasure, and opened possibilities for women to see themselves and their desires in new ways through her engagement in a variety of feminist, artistic, and sex education projects. She studied at the National Sex Forum and was a member of San Francisco Sex Information in the 1970s. She co-authored I Am My Lover, a 1978 feminist book celebrating masturbation that she created with Joani Blank and Tee Corinne. She was an early member of the Lesbian and Gay History Project, founded in late 1978 in San Francisco.

In 1981, Honey Lee received a BA in film studies from San Francisco State University. She was director and camera for Sweet Dreams starring Pat Califia (National Sex Forum, 1980), and from 1985 to the early 90s, a cinematographer for Fatale Video, the first lesbian-created erotic movie company.

She was one of the “core four,” along with Debi Sundahl, Nan Kinney, and Susie Bright, who gave On Our Backs its style and success. When it started in 1984, she proposed a “Bulldagger of the Month” centerfold for the first issue. She explained that the idea was “to stand this Playboy centerfold idea on its head from, I would say, a feminist perspective… what would I do if I was a centerfold and how can I reflect back to them our values?” Her idea was not to be “the regular kind of centerfold, but something that will make a difference, shake people up, show the other side of the mirror.” Cottrell was a contributing photographer to On Our Backs for seven years.

She photographed her lovers and friends and documented queer and kink cultures for decades with her first camera, a 35 mm Nikkormat. She was exacting and precise in the photographs and collages she created, as well as in her dark room work. She studied with Ruth Bernhard, who invited Cottrell to be her printer. In addition to I Am My Lover and On Our Backs, her still photography has appeared in publications including The Blatant Image, Coming to Power, Sinister Wisdom, and Nothing But the Girl. Her exhibitions include shows at 848 Community Space in San Francisco, the Bacchanal in Albany, California, The Gay and Lesbian Historical Society of Northern California (now known as the GLBT Historical Society), the NAME gallery in Chicago, and her images were part of Cornell University’s Speaking of Sex exhibition.

“The lesbian gaze meant that there was a contemplation,” she said, “a restraint, a sincerity and a warrior-quality. This lesbian look was compelling. While your heterosexual woman model might compel the rest of the world to look at her, a lesbian was addressing you.”

Born in Astoria, Oregon, on January 16, 1946, the oldest of two children, she grew up in Michigan. After completing a year at Michigan State University in 1964-65, Honey Lee worked for at the Technicolor photo processing lab. As she later discovered, a number of lesbians were working there, having discovered it was a fairly safe place for butch women to work. Honey Lee was invited to visit one of these women, Harriet DeVito, who had moved to New York City, and then ended up driving across country with her to California in 1966. Along the way, Honey Lee discovered what her feelings for women meant to her, and Harriet became her first lover.

Once she arrived in San Francisco, she made it her home and became deeply involved in the creative lesbian community of artists, photographers, and film-makers in the Bay Area, as well as the progressive sex education activists. She opened her apartment on Bessie Street to friends and artists, helping find jobs and shelter for people in need.

To support her artistic work, Cottrell worked in two unions. As a member of the Marine Cooks and Stewards, she was able to fulfill her dream of travel to South Pacific where her father Duane Cottrell had served in WWII. She worked as a banquet waiter in Hotel and Restaurant Employees Union in the 1980s and 90s, retiring in 2012. A proud union member, she walked many a picket line protesting the mistreatment of workers especially recent immigrant populations working as room cleaners at San Francisco hotels.

Gayle Rubin, anthropologist and theorist of sex and gender politics, says that Honey Lee:

“was never someone who put herself out front … she was more of a quiet observer, but a persistently potent presence. She had a kind of strength and solidity that seemed to anchor things around her; as if she provided the gravity that held various circling planets in their stable orbits. And she just kept generating images, events, relationships, connections.”

She loved the outdoors and studied herbal medicine, native plants, and botany. With this perspective and perhaps with her photographer’s training to notice interesting small moments of daily life, she went through her illness and death with a combination of butch swagger and serenity, a confidence that everything would be alright. She continued to direct photo shoots and art installations, and found delights in each changing day. Two weeks before her death, she had the energy one day for a road trip, lunch at a favorite Middle Eastern deli with longtime and new friends, and a walk in the redwoods. No one was surprised that she crawled under “Caution” tape and a Do Not Enter sign to get to her favorite tree, a spot she had often brought her daughter Aretha Bright.

Past lovers and family members came to visit Honey in her last 40 days, and she died at peace in her home in Santa Cruz. She is survived by her mother Patricia Cottrell, brother Michael Cottrell, and daughter Aretha Bright— and her life companions Melinda Gebbe, Amber Hollibaugh, and Susie Bright. Her papers will be cared for by the Cornell University Library Human Sexuality Collection, which will also address any questions about Cottrell’s life and work. Please direct condolences to her family at:

Mike, Judiebell, and Pat Cottrell, 3508 Greenwood Dr., Hermitage, TN 37076

Aretha Bright, POB 895, Santa Cruz, CA 95061

Susie Bright and Jon Bailiff, POB 8377, Santa Cruz, CA 95061

“I declare

That later on,

Even in an age unlike our own,

Someone will remember who we are.”

– Sappho

Cottrell’s artist statement: https://www.cla.purdue.edu/waaw/corinne/Cottrell.htm

Guide to the first part of her archives: http://rmc.library.cornell.edu/EAD/htmldocs/RMM07822.html

Sept. 6, 2015 Recording: https://youtu.be/o30jpQIwcBw

A huge thank-you to the inimitable Jiz Lee for the tireless promotion of fisting. #FistingDay is a big part of it.

A huge thank-you to the inimitable Jiz Lee for the tireless promotion of fisting. #FistingDay is a big part of it.

Honey Lee Cottrell: A Life

Thursday, October 8th, 2015The following is the obituary of Honey Lee Cottrell written by Brenda J. Marston of the Human Sexuality Collection, Cornell University.

Honey Lee Cottrell. 1978. Image by Tee Corinne.

Honey Lee Cottrell, a visionary photographer and filmmaker who pioneered lesbian erotica in the 1980s through her contributions to the women’s sex magazine On Our Backs, died on Monday, Sept. 21, of pancreatic cancer.

Cottrell revolutionized the female nude, validated women’s right to pleasure, and opened possibilities for women to see themselves and their desires in new ways through her engagement in a variety of feminist, artistic, and sex education projects. She studied at the National Sex Forum and was a member of San Francisco Sex Information in the 1970s. She co-authored I Am My Lover, a 1978 feminist book celebrating masturbation that she created with Joani Blank and Tee Corinne. She was an early member of the Lesbian and Gay History Project, founded in late 1978 in San Francisco.

In 1981, Honey Lee received a BA in film studies from San Francisco State University. She was director and camera for Sweet Dreams starring Pat Califia (National Sex Forum, 1980), and from 1985 to the early 90s, a cinematographer for Fatale Video, the first lesbian-created erotic movie company.

She was one of the “core four,” along with Debi Sundahl, Nan Kinney, and Susie Bright, who gave On Our Backs its style and success. When it started in 1984, she proposed a “Bulldagger of the Month” centerfold for the first issue. She explained that the idea was “to stand this Playboy centerfold idea on its head from, I would say, a feminist perspective… what would I do if I was a centerfold and how can I reflect back to them our values?” Her idea was not to be “the regular kind of centerfold, but something that will make a difference, shake people up, show the other side of the mirror.” Cottrell was a contributing photographer to On Our Backs for seven years.

She photographed her lovers and friends and documented queer and kink cultures for decades with her first camera, a 35 mm Nikkormat. She was exacting and precise in the photographs and collages she created, as well as in her dark room work. She studied with Ruth Bernhard, who invited Cottrell to be her printer. In addition to I Am My Lover and On Our Backs, her still photography has appeared in publications including The Blatant Image, Coming to Power, Sinister Wisdom, and Nothing But the Girl. Her exhibitions include shows at 848 Community Space in San Francisco, the Bacchanal in Albany, California, The Gay and Lesbian Historical Society of Northern California (now known as the GLBT Historical Society), the NAME gallery in Chicago, and her images were part of Cornell University’s Speaking of Sex exhibition.

“The lesbian gaze meant that there was a contemplation,” she said, “a restraint, a sincerity and a warrior-quality. This lesbian look was compelling. While your heterosexual woman model might compel the rest of the world to look at her, a lesbian was addressing you.”

Born in Astoria, Oregon, on January 16, 1946, the oldest of two children, she grew up in Michigan. After completing a year at Michigan State University in 1964-65, Honey Lee worked for at the Technicolor photo processing lab. As she later discovered, a number of lesbians were working there, having discovered it was a fairly safe place for butch women to work. Honey Lee was invited to visit one of these women, Harriet DeVito, who had moved to New York City, and then ended up driving across country with her to California in 1966. Along the way, Honey Lee discovered what her feelings for women meant to her, and Harriet became her first lover.

Once she arrived in San Francisco, she made it her home and became deeply involved in the creative lesbian community of artists, photographers, and film-makers in the Bay Area, as well as the progressive sex education activists. She opened her apartment on Bessie Street to friends and artists, helping find jobs and shelter for people in need.

To support her artistic work, Cottrell worked in two unions. As a member of the Marine Cooks and Stewards, she was able to fulfill her dream of travel to South Pacific where her father Duane Cottrell had served in WWII. She worked as a banquet waiter in Hotel and Restaurant Employees Union in the 1980s and 90s, retiring in 2012. A proud union member, she walked many a picket line protesting the mistreatment of workers especially recent immigrant populations working as room cleaners at San Francisco hotels.

Gayle Rubin, anthropologist and theorist of sex and gender politics, says that Honey Lee:

“was never someone who put herself out front … she was more of a quiet observer, but a persistently potent presence. She had a kind of strength and solidity that seemed to anchor things around her; as if she provided the gravity that held various circling planets in their stable orbits. And she just kept generating images, events, relationships, connections.”

She loved the outdoors and studied herbal medicine, native plants, and botany. With this perspective and perhaps with her photographer’s training to notice interesting small moments of daily life, she went through her illness and death with a combination of butch swagger and serenity, a confidence that everything would be alright. She continued to direct photo shoots and art installations, and found delights in each changing day. Two weeks before her death, she had the energy one day for a road trip, lunch at a favorite Middle Eastern deli with longtime and new friends, and a walk in the redwoods. No one was surprised that she crawled under “Caution” tape and a Do Not Enter sign to get to her favorite tree, a spot she had often brought her daughter Aretha Bright.

Past lovers and family members came to visit Honey in her last 40 days, and she died at peace in her home in Santa Cruz. She is survived by her mother Patricia Cottrell, brother Michael Cottrell, and daughter Aretha Bright— and her life companions Melinda Gebbe, Amber Hollibaugh, and Susie Bright. Her papers will be cared for by the Cornell University Library Human Sexuality Collection, which will also address any questions about Cottrell’s life and work. Please direct condolences to her family at:

Mike, Judiebell, and Pat Cottrell, 3508 Greenwood Dr., Hermitage, TN 37076

Aretha Bright, POB 895, Santa Cruz, CA 95061

Susie Bright and Jon Bailiff, POB 8377, Santa Cruz, CA 95061

“I declare

That later on,

Even in an age unlike our own,

Someone will remember who we are.”

– Sappho

Cottrell’s artist statement: https://www.cla.purdue.edu/waaw/corinne/Cottrell.htm

Guide to the first part of her archives: http://rmc.library.cornell.edu/EAD/htmldocs/RMM07822.html

Sept. 6, 2015 Recording: https://youtu.be/o30jpQIwcBw

Tags:Honey Lee Cottrell

Posted in Fatale News, Lesbian Life, Lesbian Sex, Life Commentary | No Comments »